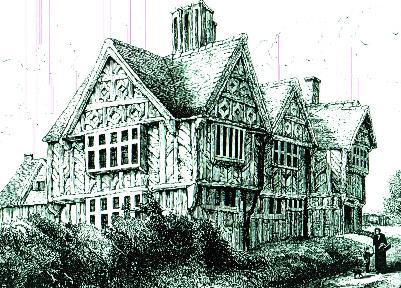

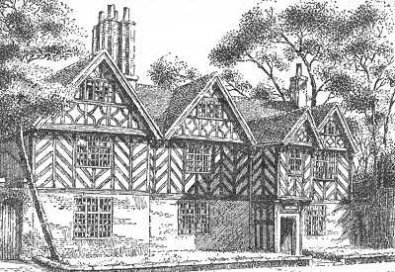

Stratford House is extraordinary as a four-hundred year old survival of a time when the population of Birmingham was only about 3000; it was built in the middle of the countryside at the time of Great Rebuilding.

1601

1643

The rural idyll would most certainly have been interrupted by the Civil War most especially during the The Battle of Birmingham in 1643. Prince Rupert set up his headquarters at the Old Ship Inn and on the rising ground to the left, near to the position taken up by the townsmen in their attack on the Royalist forces, he would have seen the quaint old half-timbered Camp Hill Farmhouse. Ruperts Cavaliers, consisting of 1,200 horse and 700 foot came in from Stratford and Alcester and opened the attack early in the afternoon on the 3rd April. Twice they were beaten off by 140 musketeers aided by townsmen with any weapon to hand who manned hastily raised barricades. Unable to stage a genuine defence of the town the defenders waged a short-lived guerrilla campaign, before escaping over hedges and boggy meadows and hiding their arms. Once the Royalist forces had gained possession of the town, they fell upon it with savagery and relish. Whether their loyalty was to the King or to Cromwell, the Rotten household would certainly have seen the fierce struggles and the Birmingham Butcheries on that Easter Monday.

1696

The house was passed from father to son until, on July 2nd 1696 when it was sold by Ambrose and Bridgetts great grandson to William Simcox for £600. The Simcox family was then in ownership until 1926 and in occupation until 1854.

1719

As early as 1719, well before the advent of board schools, the Simcox family appreciated the advantages of education as George Simcox demonstrates: God give him grace there one to Look and not to Look but understand that learning is better than house or land when house and land is gone and spent then Learning is most excellent. Around 150 years after the Civil War the house witnessed more unrest. 1791 was the year of the Birmingham Riots when the houses of Dissenters were attacked and burnt. Camp Hill Farm survived. This was probably because the Simcox family were Church of England (they were later associated with the building of Holy Trinity) or else they paid the rioters off with drink and money. Certainly from the top of Camp Hill the Simcoxs must have been able to se their neighbours houses being destroyed. Mary Simcox was the last member of the family to live in the house, but the Simcox family kept it for sentimental reasons in spite of the expense of upkeep. For sixty years after her death in 1854, it was used as a girls school under a variety of owners. The school bell, vestiges of which are still visible at the back of the house, is a reminder of this use. It was during this time that the house came to be known as Stratford House.

1831

By 1831 the population of Birmingham had grown to 170,000. After the Birmingham & Gloucester Railway cut the estate in half in 1838 the farmland was gradually eaten away by Camp Hill Goods Yard. The 1889 O.S. map shows the whole Simcox estate laid out with tunnel back houses (the remaining fields on the other side of Stratford Road had been sold by J W Simcox), probably designed for lower middle class people. Stratford House was now in the middle of the streets of Brummagem. By then the Camp Hill Station was a very busy station both for goods and for third-class passengers. Live cattle, pigs and sheep would come off the train and be put into the holding pens awaiting their journey driven by drovers into the Smithfields market of Birmingham. People who witnessed this told how the drovers used their dogs to block off the side streets to stop the animals from straying. Bulls had to have especially skilled handling. The many horses that would have been needed to serve the goods station probably provided a good market for the fodder produced on Camp Hill Farm. John Simcox remembered my brother and myself, as small boys, riding on the wagon horses bringing home to Camp Hill the loads of hay from the far meadows. Thus during the second part of the nineteenth century and with the advent of the Industrial Revolution Birmingham rapidly expanded and the house became part of the city landscape.

1896

Writing in 1896 J.W. Simcox gives us the most valuable and personal insight into life at Stratford House over the preceding two hundred years including his own memories of life in what he knew to be a farm homestead. The land was farmed until 1854. One of J W Simcoxs earliest memories confirms one of the most intriguing and yet still unsubstantiated stories about the houses Civil War history: There was a huge open chimney in the kitchen, with oak settles on either side. I remember sitting there as a child at night, and hearing the wind roar in the chimney, while old Chillingworth (his grandmothers bailiff) droned monotonously from the other side of the fire, light the murmur of many bees, old tales of which I now recall nothing. There was a legend, which I may, or may not, have hear from him, but which certainly did obtain some credence, and, as I have lately learned, exists to this day, of a subterranean passage from the old house to the Ship Inn some two or three hundred yards away. This was, when I first remember it, a long, low, thatched cottage-looking place: it is now an ugly pretentious hotel a word which I detes dignified by the name of Prince Ruperts Headquarters, with a statuette of that scientific cavalier (I think I have read that he invented mezzotint) over the doorway, representing him as consisting of three parts hat & boots, and the rest sword. As respects this passage, however unless it was the original burrow of Birmingham I fail to see its value, except possibly to proscribed Royalists, of the Roger Wildrake type, in the time of the Civil War. The idea of one of these, seated in his tunnel medio tutissimus but without supplies, and full of loyalty but of nothing else- with his house at one end, and his hostelry at the other, both filled with festive enemies, is not without pathos. As some compensation, however to contemplate him under precisely opposite circumstances he might, finding himself at that ancient tavern in the small hours in the condition known, Scotice, as having the malt abune the meal have utilized this passage in lieu of a latch key, for which comfortable implement, even is then invented, his front door, being of iron- studded oak several inches thick, was ill adapted. Then one can but hope (feebly) that this arrangement would commend itself to his wife, particularly if he brought several other proscribed Royalists in a similar condition home with him. But, considering the digging and delving which has been going on for so many years in the neighbourhood, in connection with gas, sewerage, and other civilizing agents, without disclosing the existence of any passage, I shall begin before long to tremble for the truth of this legend.

1914

In 1914 it was leased to Holy Trinity Church for parish activities and social work when there were still pleasant grounds attached to the house and persons connected to the church had facilities

for tennis, bowling and other recreations.

In 1926 Stratford House was reluctantly sold to the LMS Railway by the Simcox family after the company had threatened to use their compulsory purchase powers. The LMS felt that the cost of repairs to

Stratford House was too high and they threatened to demolish it to make space for a goods yard. There was public outrage that this valuable specimen of 17th century timber work should be lost, and

the press, the Archaeological Association and members of the City Council joined with the Education Committee to try to preserve the building proposing a number of possible uses including

accommodation for a Deaf and Dumb School. The Civic Society only managed to raise one third of the funds required to purchase the house and the Railway Company regretfully felt there was no

alternative but to demolish the house. The Stratford House Preservation Fund Committee also tried to raise funds in order to purchase the old building for erection in a suburban park as accommodation

for the local Sons of Rest, but the Civic Society considered this method of preservation undesirable and disassociated itself from a proposal which would not preserve this fine old façade in situ;

the attempt failed and so once again the house was at risk. However in 1930 the railway company agreed to keep the house in situ and use the back part of it for offices and they were commended by the

Civic Society for being public spirited.

1946

By 1946 it was empty again and in disrepair although, miraculously, still standing. In 1948 the railways were nationalised but this new company wanted to demolish the house but by now this was a public issue and it was considered a crime to destroy such an old building. In August 1950 Stratford House was designated as an Ancient Monument and the following year British Railways tried to give the building to Birmingham City Council as a gift but were turned down. The future of the house was looking very bleak. Its survival is due to father and son HF and F Garratt Adams who bought and repaired it in 1954. They got a renovation grant of £500 but the majority of the money for repair came from his own pocket. The Adams family set up a small business called Camp Hill Estates Ltd to run Stratford House as a commercial proposition, although Mr Adams senior would have liked the house to be lived in. In 1981 (long after the closure of Camp Hill Station in 1963) Stratford House was again in the news. Birmingham announced its plans a new ring road that would skirt the back of the house. Despite the concerns of the houses supporters the outcome has been that the front of the house has enormously reduced traffic and now sits in a quiet backwater overlooking a village green with the Highgate Park opposite. Finally at the start of the new millennium this lovely old house which has witnessed so much has been beautifully restored to its full glory by its present owner Ben Jackson. The house has been witness to the most extraordinary events in history, not least the two world wars of the troubled 20th Century that must have rocked its foundations, and yet it survives mainly due to the fact that it has been, and still is loved and it now enjoys the full protection of the law as a Grade II* listed house. To quote the words of John Ruskin: "Therefore when we build, let us think that we build forever. It is in that golden stain of time that we are to look for the real light and colour and preciousness of architecture: and it is not until a building has assumed this character, till it has been entrusted with the fame, and hallowed by the deeds of men, till its wall have been witnesses of suffering and its pillars rise out of the shadows of death, that its existence, more lasting as it is than that of the natural objects of the world around it, can be gifted with even so much as these possess, language and of life."

2000 Onwards

Since 2000 the property has been privatley owned and has been the home to many professional businesses and charities.

In early 2016 the building was subjected to a very serious arson attack that resulted in significant works having to be undertaken. The owners took the opportunity to restore the building to its former glory and it is now in exceptional condition - contributing to the to the growth and regeneration of Birmingham

Contact us today!

07973 702 861

enquiries@stratfordhouse.net